The ADHD Brain

.png)

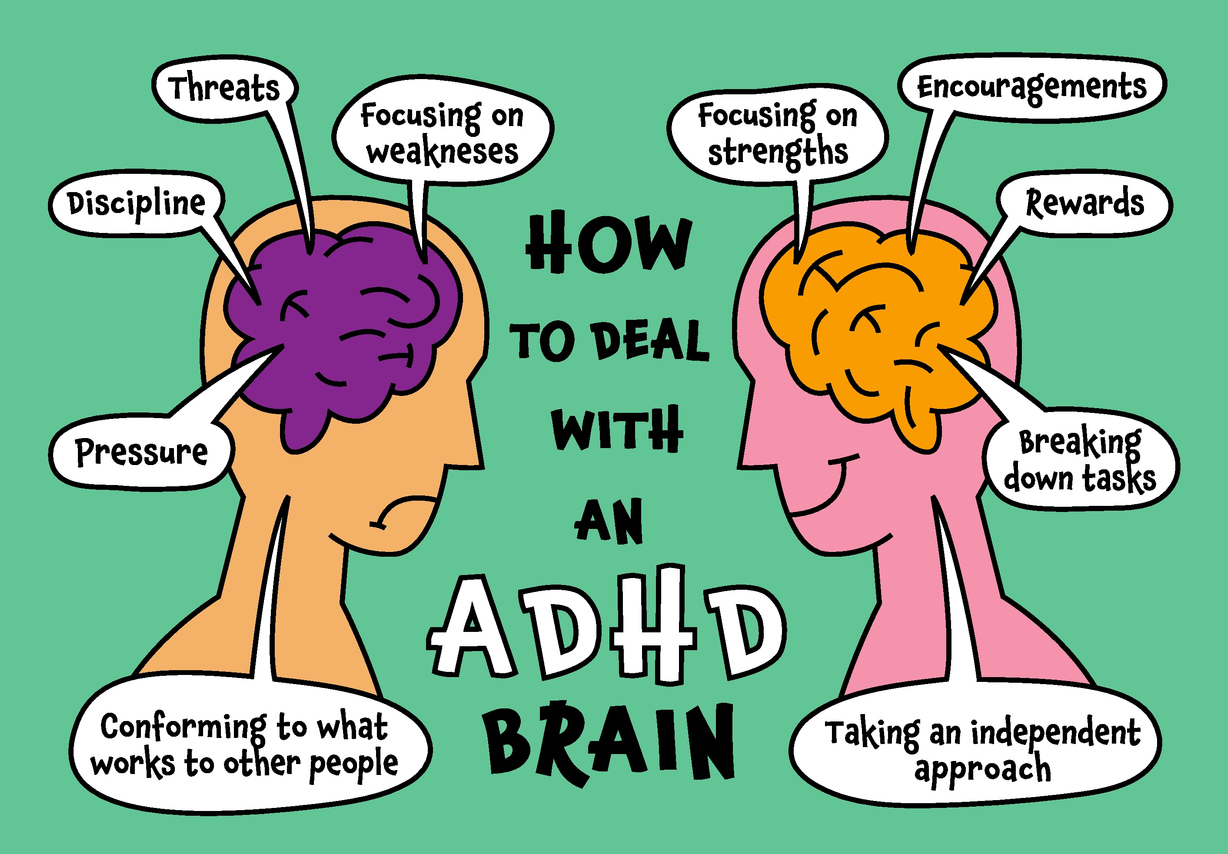

Wondering why you can’t do life the “typical” way? You’re not lazy or broken. ADHD is caused by key differences in how the brain is built and how it works.

Understanding ADHD as Neurodiversity

ADHD is a neurodevelopmental condition, meaning it starts early on in brain development and affects how you focus, manage tasks, control impulses, and regulate emotions (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). It’s one of the many forms of neurodiversity, where the brain works in unique but equally valid ways. A neurotypical brain follows more expected patterns of thinking and behaviour. A neurodiverse brain, like in ADHD, may process information in ways that are more creative, fast-moving, or nonlinear. Furthermore , there are unique differences in the structure, chemistry, and networks of the ADHD brain.

It’s essential to note that one isn’t better than the other, but just different.

Let’s take a closer look at how the ADHD brain actually works.

The ADHD Brain Looks a Little Different

Brain imaging studies show that people with ADHD often have differences in the size and activity of certain brain regions. These include:

- The prefrontal cortex, which is involved in attention and decision-making

- The basal ganglia, which important for motivation and motor control

- The cerebellum, which helps with timing and coordination (Cortese et al., 2012; Hoogman et al., 2017).

In addition to these structural differences, ADHD brains also show differences in how efficiently different brain areas work together. For example, in a neurotypical brain, the brain smoothly switches between a “resting mode” (used when daydreaming or thinking freely) and a “focus mode” (used when paying attention to a task). In ADHD, that switch doesn’t always happen as quickly or effectively. As a result, it can be harder to stay focused or shift into a task-ready state when needed (Cortese et al., 2012).

Team Voices: Here is what one of our providers at Cognito has to say:

“For me, understanding my ADHD wiring was a turning point. I decided to stop trying to 'fix' myself and instead let go of the pressure to do things like everyone else or compare myself to others. This shift has brought me a sense of relief and greater self-acceptance. Instead, I started designing systems that work for me, rather than forcing myself into a box or expecting my brain to function in ways it never has. I realized ADHD isn’t a flaw; it’s simply a different operating system. Learning how mine runs has helped me really thrive on my own terms while still getting things done that need to be done!” – Nicole, CBT Team Co-Lead

The Brain's Chemistry Is Different Too

ADHD is also linked to differences in neurotransmitters; these are the brain’s chemical messengers. Two key ones involved in ADHD are dopamine and norepinephrine, which play roles in attention, motivation, and reward (Pliszka, 2005). In ADHD brains, these chemicals may be present in lower amounts or may not work as efficiently, making it harder to stay motivated or complete tasks that don’t feel interesting.

People With ADHD Often Feel Understimulated

People with ADHD often struggle with executive functioning, which are the skills that help you start tasks, stay organized, manage time, and control impulses. These functions are managed by the prefrontal cortex, which tends to develop more slowly in people with ADHD (Shaw et al., 2007). This can explain why things like following routines, remembering steps, or waiting your turn can be harder, not because of a lack of effort, but because the brain's control system is wired differently.

ADHD Affects Emotions Too

Many people with ADHD also feel emotions more intensely and may find it hard to manage frustration, disappointment, or excitement. This is linked to how the amygdala and prefrontal cortex communicate. Emotional dysregulation is now recognized as a common part of ADHD, not just a side effect (Shaw et al., 2014).

Some researchers also believe that people with ADHD experience under-arousal where their brains may feel bored or restless more easily. As a result, they might seek stimulation by moving, fidgeting, or seeking novelty.

What This Means for You

Understanding how the ADHD brain works can help reduce shame and self-blame. ADHD isn’t a failure of willpower but rather a brain-based difference. With the right support, tools, and strategies, people with ADHD can succeed in school, work, relationships, and life.

Brains come in all kinds of wiring. ADHD is one form of neurodiversity, and when we understand it better, we can make space for different ways of thinking and thriving.

If you’d like to know more about how Cognito could support your ADHD brain, check out this blog post, The Role of CBT in ADHD Management or visit our website.

Written by: Anna Spilker

References:

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing.

Cortese, S., Kelly, C., Chabernaud, C., Proal, E., Di Martino, A., Milham, M. P., & Castellanos, F. X. (2012). Toward systems neuroscience of ADHD: A meta-analysis of 55 fMRI studies. American Journal of Psychiatry, 169(10), 1038–1055. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.11101521

Hoogman, M., Bralten, J., Hibar, D. P., Mennes, M., Zwiers, M. P., Schweren, L. S., ... & Franke, B. (2017). Subcortical brain volume differences in participants with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in children and adults: A cross-sectional mega-analysis. The Lancet Psychiatry, 4(4), 310–319. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(17)30049-4

Pliszka, S. R. (2005). The neuropsychopharmacology of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Biological Psychiatry, 57(11), 1385–1390. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.08.026

Shaw, P., Eckstrand, K., Sharp, W., Blumenthal, J., Lerch, J. P., Greenstein, D., ... & Rapoport, J. L. (2007). Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder is characterized by a delay in cortical maturation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 104(49), 19649–19654. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0707741104